Andrew Roberts’ spectacular new biography, “Napoleon: A Life” shows how Napoleon Bonaparte won his battles, engineered his own political ascent and left an enduring imprint on the modern world.

‘Napoleon: A Life’

by Andrew Roberts

Viking, 926 pp., $45

Napoleon Bonaparte, France’s early 19th century self-declared “emperor” was certainly extraordinary. But whether he was an extraordinarily talented executive who laid the foundations of modern France (and beyond) or an extraordinarily egotistic despot responsible for death and destruction on a scale almost unmatched in European history (until the rise of Nazi Germany) is a debate that continues to flourish to this day.

Andrew Roberts’ “Napoleon: A Life” is a stunning 920-page overview of Napoleon’s rise and almost as dramatic fall. Although there surely are as many biographies of Napoleon as years since his death, Roberts is the first biographer to utilize the recent publication of Napoleon’s 33,000 surviving letters. His careful scholarship is breathtaking. He researched the book in 69 archives, libraries and museums in 15 countries and personally walked 53 of Napoleon’s 60 battlefields. That meticulous research pays off in a fascinating study of Napoleon’s contributions to the modern world (for better or worse).

Born on Aug. 15, 1769, in Ajaccio, Corsica, Napoleon won a royal scholarship to a military school in France and ultimately was commissioned into an artillery regiment in 1785. He embraced the French Revolution and won recognition by recapturing Toulon from French Royalists. He rose quickly through the military ranks, ultimately taking command (at 26 years old) of the French Army of Italy against the Austrians, crushing them with a brilliant display of strategic deployment of his forces.

He led the French invasion of Egypt and, aided by a decidedly one-sided propaganda campaign, returned to Paris to a thunderous hero’s welcome. With unmatched political finesse, he engineered a coup that installed him as one of three members of the ruling Consulate, then as First Counsel, and ultimately as Emperor.

Along the way he married Josephine de Beauharnais, the widow of a guillotined royalist. She was older, far more sexually experienced, and neither loyal nor discreet. But Napoleon adored her anyway and forgave her, even after he discovered her numerous affairs. Napoleon enjoyed the company of more than 22 mistresses, so he hardly had grounds to complain.

Napoleon’s staggering impact on the modern world is difficult to overstate. As Roberts notes, “the ideas that underpin our modern world — meritocracy, equality before the law, property rights, religious toleration, modern secular education, sound finances and so on — were championed, consolidated, codified and geographically extended by Napoleon.” He rationalized local government administration, encouraged science and the arts, abolished feudalism and codified the law.

But above all, Napoleon was a warrior. Although often criticized for his boundless ambition and ego, war was declared on him far more often that he declared war on others. His military campaigns and strategy are studied to this day. His decision to invade Russia in 1812 was a fatal mistake, but hardly irrational. The French had defeated the Russians three times between 1799 and 1812, he had fought and won in blizzard conditions, and had won battles at the far end of long lines of communications at Austerlitz and Friedland. But he lost 400,000 of his men in Russia, more than 100,000 of them from a typhus epidemic. It was the sheer size and ferocity of his army that led the Russians to strategically retreat, avoiding battle and drawing Napoleon and his army ever deeper into the Russian heartland — and winter.

This book is simply spectacular. Roberts writes beautifully and, aided by meticulous historical research, brings Napoleon alive before the reader, with grapeshot and cannon fire splattering across the page.

Napoleon never lacked confidence. After his defeat at Waterloo and banishment to St. Helena, he was asked why he had not taken Frederick the Great’s sword when he was in Russia. He replied, “Because I had my own.”

Category: French History

-

‘Napoleon’: supreme strategist in governing, love and war

-

‘How the French Invented Love’: 900 years of living, loving and liaisons

Marilyn Yalom’s lively “How the French Invented Love: Nine Hundred Years of Passion and Romance” documents the French obsession with love and sex in literature and life.

‘How the French Invented Love: Nine Hundred Years of Passion and Romance’

by Marilyn Yalom

HarperPerennial, 416 pp., $15.99

Few things define the French more vividly than romance and love.

For hundreds of years, the French have obsessed over love and sex, in art, literature and poetry. From the middle ages to modern day, French culture has played an outsized role in fashioning concepts of chivalry, gallantry, and appropriate (and sometimes inappropriate) relations between men and women. Even in English, we turn to French to speak of love: “French kissing,” “liaison,” or “rendezvous.”

In “How The French Invented Love” author Marilyn Yalom surveys French literature through the ages, tracing the development of the concept of “love” and “romance.” A French professor working on “gender research” at Stanford University, she is well suited to the task, displaying an easy familiarity with 900 years of French literature.

To the French, the story of Abelard and Heloise is as familiar as Romeo and Juliet are to Americans or the British. In 1115, he was a 37-year-old cleric, philosopher and famously popular teacher; she was a brilliant 15-year-old niece of a church official. They became lovers, were married, then became victims of an angry uncle who castrated Abelard. She became a nun; he a monk. But their correspondence burned with a passion she could not quench, and 900 years later, still smolders.

Edmond Rostand’s play, Cyrano de Bergerac, is the most frequently performed French play in history. Cyrano, witty and articulate, but cursed with coarse looks, sacrificed his own love for Roxane to assist his friend Christian, who coveted the same woman but who had no gift for language. With Cyrano’s help, Christian won her to his side, then died a tragic death. Roxane retreated to a convent and only after many long years and on his deathbed does she discover that it was Cyrano all along who spoke for Christian.

Yalom surveys the delicate art of seduction, perfected by the French royalty who seemingly spent more time focused on the opposite sex than the, ahem, affairs of state. In 1782, for example, Choderlos de Laclos published “Les Liaisons Dangereuses,” a radically different portrayal of love. Far from a romance, the novel traces the story of two ex-lovers who use sex as a competitive game, leaving their degraded “conquests” in their wake. The book remains required reading in French high schools (imagine the outcry if added to the curriculum of an American high school). But it was an apt critique of the Ancien Régime on the eve of the French Revolution.

Yalom covers the famous love letters of star-crossed lovers, gay love, republican love in the time of the Revolution, and the “sentimental education” offered by the sexual initiation of a younger man by an older woman. It’s a fascinating short course through French literature, history and changing attitudes toward sex and love, all of which heavily influenced western thought over the last millennium.

But even so, French and American perspectives remain markedly different. Americans scratched their heads in wonder at the state funeral for French President François Mitterand in 1996, attended by both his wife, Danielle, and his longtime mistress, Anne Pingeot. The French, in turn, were baffled by the impeachment of an American President for an office dalliance with an intern.

But as Yalom demonstrates, these are the very questions that have been debated throughout history, much of it defined by French literature, culture and language. The French may not have “invented” love but they certainly have spent a lot of time exploring its application. -

Young American in Paris tale is lightweight but amusing

“Paris, I Love You But You’re Bringing Me Down” is young New Yorker Rosecrans Baldwin’s short and often clichéd tale of moving to Paris with his wife only to find it is a lot different from New York.

‘Paris, I Love You But You’re Bringing Me Down’

by Rosecrans Baldwin

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 304 pp., $26

In his new book, “Paris, I Love You But You’re Bringing Me Down,” Rosecrans Baldwin, a young New Yorker, recounts moving to Paris with his wife to take a job with a French advertising firm.

A thorough Francophile from a young age, Baldwin is ecstatic when he arrives, thrilled to be living in the City of Light, surrounded by the stunning architecture, food and people. But reality soon sets in as it dawns on him that — quelle horreur — the city is actually French, and not only the language but the culture is different from, say, New York.

You can, of course, imagine the shock.

Baldwin struggles with mastering French in a business setting (it gave him migraines). As he recounts, “First day on the job, my French was not super. I’d sort of misled them about that.”

He struggles learning to master the informal kiss that is the typical greeting, even in business settings, and dealing with infamous French bureaucracy. He describes it all as if it were a daunting challenge rather than a rather tame exercise in cultural differences. This is, apparently, a sheltered young man. Think Paris is different from New York?

The book is an entertaining but lightweight addition to a genre that is already crushed by the number of Americans “living abroad” books (further subdivided into the French and Italian versions). It’s more than a little cliché to describe how terribly difficult it is to move to a foreign country where they don’t speak English all the time. But honestly, this borders on downright silly as virtually everyone in Paris speaks English at some level and most visitors hear almost more English than French on the street. There are McDonald’s everywhere. The difficulty isn’t finding someone who speaks English; it’s trying to escape the expanding American cultural dominance abroad.

Almost worse, Baldwin spends chapters on how the French dress, their notoriously sexy ads, and difficulties involved in renting an apartment. Yes, all of that is different from what one might find in New York or Chicago. That’s the point of living abroad, isn’t it?

Ultimately, Baldwin moves past the cliché, but just barely. The book is worth reading only because it’s thankfully short and doesn’t require a lot of serious attention.

As a friend once said of her sister: “She talks a lot but says so little, it gives you time to rest.” Still, it’s a worthy read, if only to get a glimpse of what it’s like to live on a budget as an overwrought young ad executive in Paris at 29. -

David McCullough’s ‘The Greater Journey’: How France nurtured the American experiment

David McCullough’s ‘The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris’ chronicles the outsize influence France, particularly Paris, had on American writers, artists, politicians and scientists in the 19th century.

The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris’

by David McCullough

Simon & Schuster, 576 pp., $37.50

There are few countries with as much in common as the United States and France. The French provided not only critical support to the American colonies fighting for their freedom but also much of the philosophical foundation for the young Republic. Long after the revolutionary dust settled, France continued to nurture the American experiment.

From 1830 to 1900, a tide of influential Americans – artists, writers, painters and doctors – braved the treacherous journey across the Atlantic to visit Paris. What they saw profoundly changed not only the travelers, but also America itself.

Charles Sumner studied at the Sorbonne, astonished to see black students treated as equals and, as a result, became an unflinching voice against slavery as the U.S. senator for Massachusetts, beaten nearly to death by a South Carolina senator on the floor of the Senate for his views.

James Fenimore Cooper (“The Last of the Mohicans”) wrote some of his most significant works in Paris, working with his close friend Samuel F.B. Morse. Morse, inspired by the French communication system of semaphores, invented the modern electrical telegraph and his famous code and radically changed communications globally.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Mark Twain and Henry James all lived and worked in Paris. Charles Bulfinch, the architect who designed the U.S. Capitol, was inspired by touring Parisian monuments in 1787 with Thomas Jefferson, then the American minister to France.

In “The Greater Journey,” David McCullough, the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian, captures this flood of doctors, writers, artists and free spirits who coursed through Paris. Moving chronologically, he tells the story through the eyes of these young travelers, astonished by the beauty of the city before them.

McCullough’s skill as a storyteller is on full display here as he relates the treacherous Atlantic crossing, the horse-drawn carriages and less-than-ideal plumbing that greeted the travelers, many of whom had little exposure to anything outside the rural U.S. For aspiring artists who had never even seen a copy of the masterpieces of the Old World, the experience of an afternoon at the Louvre was enough to bring them nearly to their knees.

The idea of telling the story of the French cultural contribution to America through the eyes of a generation of aspiring artists, writers and doctors is inspired, and McCullough draws on untapped historical sources to tell the story, against the roiling backdrop of a French military coup and a new Emperor (Louis Napoleon), a disastrous war with Germany that included a siege of Paris (setting the stage for WWI) and the horrific Paris Commune that followed.

But the effort in several ways falls disappointingly short of its early promise. The historical narrative is disjointed. McCullough mentions Andrew Jackson’s defeat by John Adams, only to jarringly describe a toast to President’s Jackson’s election only pages later, without explanation. (Adams narrowly won in 1824 in an election decided by the House of Representatives but lost his re-election bid four years later to Jackson – but you wouldn’t know it from this book.) French history, similarly, unfolds with only cursory explanation of the events.

Second, McCullough’s focus on such a wide cast of characters renders the portrait of each one superficial, scattered by a wide historical lens and large cast. Exciting accomplishments, tragic losses and almost everything in between is lost.

At the same time, however, McCullough focuses inordinate attention on detailed descriptions of sculpture or paintings, distracting from the larger point McCullough is making: the powerful influence on American painting, sculpture, writing and medicine wielded by a small but hugely influential group who braved the dangers of transatlantic travel and brought home radical and transformative new ideas.

Perhaps an 80-year history of France, told through the eyes of dozens of American visitors, can only be told with such a blurred historical detail. It’s a shame, though – with the absurd memory of “freedom fries” and hostility to one of our closest allies still ringing in our ears, it’s worth remembering the French contribution to American art, politics, science and medicine. But even with its faults, McCullough deserves credit for finding a compelling and largely untold story in American history. -

A French connection built from reading, riding, researching

‘The Discovery of France: A Historical Geography from the Revolution to the First World War’

by Graham Robb

Norton, 454 pp., $27.95

Most of us have a reasonably clear sense of France and its history. Invaded by the Romans and ruled by a series of royal families, France was rocked by a bloody Revolution, ruled by an emperor named Napoleon and made home to the Eiffel Tower, ultimately becoming the classic tourist destination (before the Euro made it too expensive to visit). But this modern conception of France is not only incomplete, but fundamentally misconceived.

Almost everything that makes France “French” is a more or less modern invention. French as a language, for starters, was not widely spoken throughout France itself until well after the French Revolution. Instead, peasants throughout the countryside spoke a hodgepodge of differing languages and dialects. Even in the late 1700s, a traveler leaving the city limits of Paris typically required a translator to be understood and, farther south, would have difficulty even identifying the language he or she was hearing. Indeed, just over 100 years ago, French was a foreign language to nearly 80 percent of the population.

Graham Robb, a historian and author of several acclaimed biographies, provides a ground-level historical geography of France from the Revolution through the First World War. An avid bicycle rider, Robb researched the book by riding more than 14,000 miles throughout France and spending four years in the library. What he discovered was how little of what one might consider “France” existed only a couple of centuries ago.

Indeed, authorities didn’t even attempt to map the country until the mid-18th century. Even then, the cartographers encountered stiff hostility from villagers suspicious of “foreigners” with strange devices.

Large parts of France weren’t even part of the country until relatively recently. Brittany, for example, didn’t become part of France until 1532, when Queen Anne of Brittany married into the Royal family and brought the Celtic province as her dowry. France, similarly, didn’t acquire Alsace and Lorraine until the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. Nice and Savoy didn’t become part of France until 1860. As Robb notes, “the propaganda of French national unity has been broadcast continuously since the Revolution, and it takes a while to notice that the tribal divisions of France were almost totally unrelated to administrative boundaries.”

The Revolution, together with the introduction of modern transportation and communication systems, brought enormous pressures to bear on provincial culture. In the provinces, being “patriotic” or “educated” often meant denigrating one’s own culture, language and customs.

Little of what once existed survives to this day. On the marsh lands of southwest France, shepherds on 10-foot stilts once covered dozens of miles of heath in a day. Deserts covered portions of the interior. Seasonal migrations of masons and other skilled workers traveled the footpaths toward Paris and employment. Highly trained dogs in the north smuggled goods to evade taxes.

With much of the country transformed by modern agriculture, the French language imposed from above and modern transportation leaving villages to collapse into neglect, many of the curiosities of ancient France simply vanished into the slipstream of history.

Robb’s book offers a glimpse into that forgotten past, from evidence found at bike level in obscure corners of the country most of us are unlikely to visit. And for that meticulous research, he deserves a standing ovation. He could, however, have benefited greatly from a strong editor with an ample supply of red pencils, as the book suffers from occasional numbing detail, arcane asides and a less-than-transparent organization. But for those in search of a remembrance of things past, to paraphrase Proust, this is a priceless glimpse into history. -

French writer doesn’t live up to his own hype

Traveling in the Footsteps of Tocqueville

Random House; translated by Charlotte Mendel

308 pp., $24.95

As the self-proclaimed greatest living French philosopher and “prophet,” and with the chutzpah to compare himself to Alexis de Tocqueville, Jean-Paul Sartre and Jack Kerouac, Bernard-Henri Lévy has a lot to live up to. Instead of doing so, in “American Vertigo: Traveling in the Footsteps of Tocqueville,” (Random House, 308 pp., $24.95, translated by Charlotte Mendel), he presents a textbook demonstration of the adage that those who boast the loudest most often have the least to boast about.

Lévy, a prolific French author-activist, spends his time courting the press, pursuing various causes and relaxing by the pool at his Marrakech palace with his movie-star wife, Arielle Dombasle. The author of some 30 books, Lévy is breathlessly described by his publisher as no less than “France’s leading writer” and by Vanity Fair magazine in a recent profile as a “superman and prophet: We have no equivalent in the United States.”

Excuse me? If this is “France’s leading writer,” then that’s a sad statement indeed for the state of the French Academy.

Lévy was commissioned by the Atlantic Monthly magazine to travel the United States, in an effort to duplicate Alexis de Tocqueville’s own journey, made famous by his 1831 book, “Democracy in America.” De Tocqueville’s thoughtful observations about America and the American democratic experiment are among the most influential political analyses ever written on the subject. The book, in print for more than 150 years, is a classic of political literature and few, if any, foreign writers have ever come close to de Tocqueville’s trenchant observations.

The suggestion that Lévy, the playboy gadfly of the French intellectual set, could “follow in his footsteps” is a dubious concept from the outset, and the actual product proves even worse.

Lévy’s overblown style combines ceaseless name-dropping, merciless redundancy and horrific verbosity in one toxic combination. An editor could have easily reduced this entire volume by some 75 percent without losing a single important thought. Lévy manages, in the introduction, to launch sentences that ramble through villages, streams and forests without punctuation, pause, or even the suggestion of a period for nearly a full page. Whew. Is this mash-up of thoughts supposed to impress the reader or simply beat him or her into submission?

Worse, Lévy has the gall to compare himself, at the outset, with both de Tocqueville and Jack Kerouac. He would have profited mightily by setting his sights just a bit lower. Lévy set out to follow de Tocqueville’s travels and, with a handful of exceptions, followed his path. He devotes short chapters to describing what he found. From the monstrosity of Mount Rushmore to the foggy city of San Francisco, Lévy catalogs a variety of American sights, cities and movements. He devotes an adoring chapter to Seattle, in which he declares that he “loved absolutely everything about Seattle” (although he uncharacteristically manages to convey his thoughts on the subject a pithy three pages). But for all the arm-waving, the author provides precious little political analysis or thoughtful observation about his travels, America after the turn of the millennium, or its status as the world’s only superpower on a lonely nation-building mission to remake the world (or at least parts of it). The book reads more like a compendium of jumbo postcards written by a pompous European observer with a short attention span and an apparently straying intellectual curiosity. Surely, we can do better than this. France arguably laid the very foundation of American democracy — funding the revolution when there were precious few others willing to underwrite such a ragtag collection of rebels; contributing some of the most potent strands of political theory embraced by the revolutionaries; and, half a century later, contributing an astonishingly thoughtful observer, in de Tocqueville, to catalog the American experiment as it unfolded. Unfortunately, however, Lévy’s return engagement fails to provide any fresh insight. Instead, it serves as a rather dramatic reminder (at least for those intrepid enough actually to finish the book) that the value of an idea or an observation is far more often measured by its perceptivity or originality, rather than the lifestyle of its author or the sheer volume of ink used in its printing. -

‘La Belle France’: Modern France shaped by historic loss

‘La Belle France: A Short History’

by Alistair Horne

Knopf, 485 pp., $30

There are few countries with a more fascinating history than France. In “La Belle France: A Short History,” Oxford historian Alistair Horne provides a breathtaking tour of French history, from its earliest kings through the Mitterand government of the 1980s.

Starting from Julius Caesar’s division of Gaul, Horne surveys the Crusades; the Dark Ages; the Plague; and endless royal succession, mendacity and extramarital sexual liaisons. Horne, no stranger to his subject, has authored nine prior volumes of French history.

Horne deals with the French Revolution in a single chapter, but then sweeps on. Napoleon Bonaparte rose to power amidst the anarchy of the Revolution. But he fatally invaded Russia in 1812, was forced back, and ultimately surrendered. He was banished to Elba, escaped, returned to power and was defeated at Waterloo, all within the so-called “Hundred Days.” From the Revolution to Waterloo took 25 years – a span of time comparable to that from the election of Ronald Reagan to today.

Internally, the restoration of the monarchy lead to repeated popular uprisings. Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, nephew of Napoleon I, seized control and declared himself “Emperor” but ultimately was defeated by Prussia, which forced a humiliating capitulation by the French at Versailles in 1871.

From there, it was a straight line to World War I, an utter calamity for France, during which she lost 1.3 million men. The United States, by contrast, lost 53,513 men in the entire conflict. Indeed, France lost more men in World War I – by a large margin – than the United States has lost in every war it has ever fought, from the Revolutionary War through the last soldier to die in Iraq, combined.

That’s no criticism of unquestionably brave American soldiers, but for much of the brutal slaughter of the Great War, they were home in Nebraska. How do you measure bravery? By sacrifice? By the willingness to stand and fight against all odds? By the war’s end, France was bereft of an entire generation of young men. That loss – 20 years later – resulted in a shocking disparity in birthrates. By the eve of World War II, four times as many militarily-capable young men were reaching maturity in Germany as in France.

Conventional wisdom would have it that the brutal peace terms dictated by France and her Allies led directly to World War II. But for France, humiliated at Versailles in 1871, this was a settling of debts. Unfortunately, not the last.

Like slow-motion footage, the book slows as it approaches the cataclysm of World War II. The devastated French sought desperately to avoid another war but devoted their attention to eastern fortifications and social unrest, rather than military preparations. The Germans, by contrast, quietly built a powerful war machine and lulled the West to sleep. When ready, Hitler sidestepped the French Maginot line and punched a 60-mile-wide hole through the French defenses, moving with astonishing speed. It was over before it began, with the French losing more than 300,000 men in the first six weeks alone.

The Germans were strictly instructed to be extremely courteous in occupied Paris, and it was only after they consolidated control that neighbors living near 74 Avenue Foch, where the Gestapo settled, were kept awake at night by the screaming from the interrogation rooms.

Some things are understood best from a great distance. French resistance to more recent calls to arms must be seen through the prism of its bloody history, and particularly its staggering losses of the last 100 years. As Santayana famously remarked, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. -

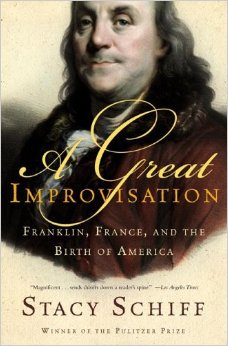

‘Franklin, France, and the Birth of America’: Revolutionary ideas, charm

‘A Great Improvisation: Franklin, France, and the Birth of America’

by Stacy Schiff

Henry Holt, 489 pp., $30

In December 1776, a decidedly seasick 70-year-old Benjamin Franklin arrived in France, seeking financial and military support for his embattled new country. During the seven years he served as the American representative in Paris, Franklin proved a masterful diplomat, manipulating the tangled European political scene to achieve what, from a distance, appears an improbable outcome: the massive support for a republic founded on democratic principles from one of the strongest monarchies in Europe.

In “A Great Improvisation: Franklin, France, and the Birth of America,” Stacy Schiff recounts the story of Franklin’s time in Paris. A Pulitzer Prize winner (for “Véra,” a biography of Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov), Schiff poured through diplomatic archives, family papers and even spy reports to reveal insights into this little-known chapter in Franklin’s life.

At the time of Franklin’s arrival in Paris, the newly declared American republic was recognized by no other countries, had few financial resources and no military allies, and was attempting to win its independence from one of the most formidable, well-armed and well-financed military powers in existence. Its citizen army was poorly equipped, on the run and suffering one defeat after another, retreating even from major metropolitan centers. To say that the colonial revolutionaries faced an uphill battle is an understatement.

Franklin’s purpose was to secure French military and economic support for the revolution. France sought to undermine England’s hegemony over North America and to support its own designs on that continent. England sought to crush the revolution and keep the French from meddling in what it considered “internal” disputes within the British empire.

Franklin deftly played one side off the other — holding out the possibility of a negotiated settlement to the British on the one hand, while cajoling a series of enormous loans, grants and military support from the French on the other. And he was spectacularly successful: During the first year of the revolution, 90 percent of the gunpowder came from France. Millions of dollars in economic aid, military uniforms and French volunteers poured across the Atlantic to support the cause. The battle of Yorktown was not only fought by brave American patriots, but also by the combined American and French armies, where the victory cry was equally “God and Liberty!” and “Vive le Roi!” The French population became passionately pro-American in what, in retrospect, plainly presaged the French Revolution itself.

When he arrived, Franklin was already well known and widely respected by the French. His unannounced arrival caused an uproar of well-wishers trodding the path to his door, and he quickly won over the Parisian population with his charm.

But even from the outset, the French-American relationship was strained in ways that continue to this day. First, cultural differences between the two countries were stark. As Schiff notes, in American society, a young lady could properly flirt until marriage, but never thereafter. The roles were almost precisely reversed in pre-Revolutionary France, where flirtation among married women was elevated to a near art form. Franklin excelled at the art and had numerous relationships (in his 70s) with a variety of French women. Moreover, class standing played a central role in defining one’s role in pre-Revolutionary France, and many French were puzzled by Franklin, a mere printer by trade, who rose to prominence on the strength of his scientific and diplomatic accomplishments.

But for all the power of the story, the biography suffers from stilted, awkward writing, almost as if written in French, or perhaps German, and then poorly translated to English. More than once, a reader is forced to reread a sentence two or three times before comprehending what Schiff was attempting to communicate. The editor here was plainly missing in action and the book suffers as a result.

Still, the story rises above even this flaw, and has special relevance today, in an era of “Freedom Fries” and blatant anti-French sentiment. Franklin, who embraced — and was embraced by — the French, recognized that, without French support, the American Republic would have quickly vanished without a trace under the bootheels of the British regular troops. Perhaps it is a timely reminder that, despite passing political trends, the bonds between America and France were forged from the outset of the Republic and can withstand even today’s unfortunate political posturing and sloganeering. For, indeed, without France, there would have been no America at all. -

‘Moscow 1812’: An overture to massive wars of modern times

‘Moscow 1812: Napoleon’s Fatal March’

by Adam Zamoyski

HarperCollins, 672 pp., $29.95

Napoleon’s 1812 invasion of Russia ranks as one of the greatest military disasters in history. The story has been told countless times and inspired Tolstoy’s “War and Peace” and Tchaikovsky’s “1812 Overture.”

But, according to “Moscow 1812: Napoleon’s Fatal March,” much of that history has been politically distorted. Author Adam Zamoyski strives to set the record straight with an objective and comprehensive account of the ill-fated invasion. And what a story it is.

At war with England, Napoleonic France controlled virtually all of Europe, spreading the subversive egalitarianism of the French Revolution and the civilizing Napoleonic Code.

Russia, in 1812, could hardly have been more different. Controlled by Czar Alexander, Russia was a backward, feudal country whose leaders were threatened equally by foreign armies and peasant uprisings. Although allied with Napoleon, French trade restrictions devastated the Russian economy, forcing Alexander to confront Napoleon or face mounting discontent at home.

Napoleon had nothing to gain from invading Russia but felt compelled to teach it – and his many “allies” – a lesson. The midsummer invasion force was the largest army ever mustered. The French army, used to foraging for food and supplies, found precious little in the Russian countryside. Dysentery, starvation and dehydration wreaked havoc before the first shot was fired.

Although Soviet historians have characterized the Russian retreat as a clever strategic trap, Zamoyski painstakingly documents the incompetence of the Russians and their terror at facing the French. Indeed, the Russians retreated until forced to fight at Smolensk and Borodino, where 70,000 were slaughtered. It was a record that would not be matched for 100 years – until the Battle of Somme in 1916.

Napoleon continued his advance, forcing the Russians to surrender Moscow itself. On foot and horseback, Napoleon’s invasion force got further than Hitler’s mechanized war machine over a century later, but it had no greater success. Moscow harbored neither the czar nor his government and, indeed, was burned by the Russians themselves, leaving Napoleon a hollow victory. By any fair measure, he had won – prevailed in every battle, controlled sections of the country and seized the capital city. But the Russians refused to surrender, leaving Napoleon to ponder his circumstances as winter stealthily approached.

As late as the end of October, Napoleon ridiculed the Russian winter as a myth used to scare small children. Within days, the temperature had dropped below zero, the snow had begun to fall, and his error was manifest.

The retreat was almost unfathomably brutal. The French troops had no winter uniforms, and what clothing and boots they had were in tatters. With little food and burdened with looted Russian treasure, the retreat passed through lands already stripped clean of nourishment. And the temperature continued an inexorable fall, ultimately reaching 35 below zero Fahrenheit.

The starving men turned frantic – cutting chunks of meat off the back legs of living horses (the dead ones were too deeply frozen to cut). The horses, nearly frozen themselves, hardly noticed. The temperature was an implacable foe. Those who slept often never awoke. Soldiers were observed frozen in place standing, sitting or lying by fires. The Russian army, meanwhile, bungled several opportunities to destroy the French army. Napoleon was nearly caught at the River Berezina, which was held by Russians on both banks and circled by troops to his rear.

Napoleon sent a diversionary force south, then headed north where 400 Dutch pontooneers worked through the night to build two bridges over the river. Standing chest deep in icy water, dodging 2-meter chunks of ice, they worked as Napoleon sat on horseback and watched them die – and make progress. Although only eight of the pontooneers returned home, the bridges were completed and the French survived.

Of the more than 600,000 French soldiers who crossed into Russia, barely 150,000 made it out alive. About 160,000 horses perished during the invasion. Counting Russian losses, nearly 1 million people died during the course of the six-month invasion.

With Napoleon in retreat, the Russians followed and, just over a year later, occupied Paris. Napoleon was eventually overthrown and exiled to Alba. Although he returned, he was ultimately defeated by the British at Waterloo and exiled to St. Helena for the remainder of his life.

But the consequences of the 1812 invasion lived on. It is difficult to grasp the extent to which our world today has been shaped by the invasion and its failure. Napoleon’s disaster emboldened Russia to extend its reach into Europe and solidified German nationalism and militarism, with devastating consequences in the following century.

This is a towering history – a thoroughly enjoyable read that is worthy of the monumental scope of its subject. Zamoyski’s writing is vivid and, perhaps more important, he knows when to let his sources speak for themselves.

If one can complain, it is simply that Zamoyski gives short shrift to the consequences and enduring legacy of the 1812 invasion and its very real impact on the political geography of today.

When Napoleon died in 1840, his body was returned to Paris, where it awaited burial. In honor of the 1812 invasion, 400 veterans silently, but eloquently, saluted their fallen leader – by spending the night on the ground around the casket as the temperature plunged to below zero. -

Memoirs of a Breton Peasant’ Countryside to battlefield: a French peasant’s life

‘Memoirs of a Breton Peasant’

by Jean-Marie Dguignet, translated by Linda Asher

Seven Stories, 431 pp., $27.95

Jean-Marie D