This isn’t a soft pedaled version of wartime service but a cold, devastating self-examination of the decidedly personal costs of war. It is creative, exhausting and illuminating, all at once. Author Matt Young will be at Elliott Bay Book Co. on Feb. 28.

“Eat the Apple”

By Matt Young

Bloomsbury Publishing, 272 pp., $26

There are several ways to react when you wake up with an aching hangover, realizing that at some point in the night you drunkenly crashed your car into a fire hydrant. Promptly signing up for the U.S. Marine Corps is perhaps the least obvious choice.

But 18-year-olds can be unpredictable and, by the time his head had fully cleared, Matt Young was a newly enrolled Marine. It was an odd way to address the damage to the fire hydrant, the car or his head. But, as he explains, “because your idea of masculinity is severely twisted and damaged by the male figures in your life and the media with which you surround yourself — that the only way to change is the self-flagellation achieved by signing up for war.”

“Eat the Apple” is Young’s bracing memoir of this time in the Marine Corps infantry. Young, who lives in Olympia and teaches at Centralia College, was deployed to Iraq three times between 2005 and 2009.

Young writes in a disconcerting first-person, present-tense narrative, perhaps well suited to the jarring and very immediate world of a Marine in training and then combat. For the more casual reader, it is disconcerting. Each chapter of the book reads almost like its own essay, only loosely connected with what comes before and after.

Young doesn’t even try to discuss the larger implications of the Iraq war, its purpose or what it might or might not have accomplished. Nor is this a critique of how the war was fought. This is not a political book and takes no position on the war, its objectives or its conduct.

Instead, this is a purely eyes-on-the-ground narrative as to what it feels like to endure basic training, to learn to bond as a team and to follow orders, however stupid they might seem to be (or actually are). The title is drawn from a Marine Corps saying, “eat the apple; (expletive) the corps,” meant both as a play on words and an insult to the Corps, often by a departing Marine.

The book contains a variety of drawings of the sort used by doctors to have patients identify the location of pain or injury but used by Young to self-diagnose his own deteriorating condition as his service continues. An entire chapter is devoted to masturbation and, among other things, its use to stay awake during guard duty.

Young’s description of his return from his first deployment is haunting and worth the price of the book alone. The flights from war-torn Iraq, to Kuwait and finally to California become increasingly disorienting in their contrast to Young’s war-torn personal experience. In a fog, he wants badly to be happy to see his family but instead drinks himself senseless, rambling about his deployment, telling them what he thinks they want to hear, unable to stop and coldly measuring the next day the distance between his old and new life. If one needs a yardstick to measure the impact of wartime service on our service members, this would be a good start.

From a grunt’s perspective, the war is a vast stretch of tedium, interrupted by sudden terror and stunning loss. Testosterone-fueled acts of misconduct followed by brutal disciplinary correction. Young ably captures a tumultuous world of honor, boredom and terror.

The effect is jarring and emotionally raw. This isn’t a soft pedaled version of wartime service but a cold, devastating self-examination of the decidedly personal costs of war. It is creative, exhausting and illuminating, all at once.

Category: Seattle Times Reviews

-

‘Eat the Apple’: a Marine’s jarring eyes-on-the-ground view of war

-

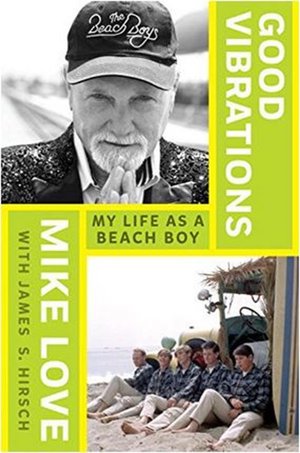

‘Good Vibrations’: Beach Boy Mike Love unloads in a contentious memoir

In his new book, “Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy,” Mike Love uses the memoir form to attempt to settle some scores.

‘Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy’

by Mike Love

Blue Rider Press, 436 pp., $28

It’s difficult to imagine a more iconic American rock band than the Beach Boys. Bursting on the scene in the early 1960s with catchy songs about the California surfing scene, the Beach Boys had a string of hits that continue to inspire generations of fans. “Surfin’ USA,” “Catch a Wave,” “California Girls,” “God Only Knows,” and dozens of other hits propelled the group to prominence.

The band included Brian, Dennis and Carl Wilson — all brothers — and their cousin, Mike Love. Under Brian’s direction, the group constructed tightly woven harmonies that spoke of life on the beach. Love was the lead singer and contributed lyrics to many of the band’s songs.

In his just-released autobiography, Love sets out to settle more than a few scores. Perhaps it’s a hazard of the genre, but the entire effort is more than a little self-serving. Love is alternately defensive, angry, self-pitying and proud. It’s dizzying just trying to keep his grudges straight.

Love has had a contentious relationship with his cousins — and many of his fans — over the years. Brian Wilson was the genius of the band, responsible for writing the stunning music, the catchy melodies and — most important — the astonishing harmonies.

Brian, though, stopped touring in 1965 (but he’s coming to Seattle soon!), instead focusing his time on creating ever more complicated songs. “Pet Sounds,” released in 1966, was largely written by Brian Wilson, with vocal overdubs recorded by the rest of the band when they returned from an overseas tour. The album is now considered one of the greatest rock albums of all time and an inspiration for the Beatles masterpiece, “Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.”

The band, under Love’s direction, continued to tour without Brian. As Brian’s music became increasingly esoteric, he began to crumble under the combined weight of public expectation, increasing drug use and evident mental instability. His planned masterpiece album, “Smile” was abandoned as Brian unraveled.

Love, meanwhile, continued to drive the band forward. But as the 1960s progressed, the Beach Boys — with their matching striped shirts — fell out of fashion and, without Brian’s contributions, the band suffered. Since then it has released several mediocre records but has largely survived as an oldies band.

Love bitterly complains that he did not receive credit for co-authoring various hits, “California Girls” among them. He sued Brian Wilson over the issue (and separately for defamation) and won a judgment declaring him the co-author of dozens of the band’s songs.

According to Rolling Stone magazine, Love “is considered one of the biggest assholes in the history of rock & roll.” Reviled for his hostility to “Pet Sounds” (he denies it), his tight gold lamé pants, his Republican sympathies (he denies it) and his vain effort to conceal his balding head in a rotating series of caps, Love is easily one of the most controversial figures in rock ’n’ roll.

Dennis Wilson died in 1983, in a diving accident. Carl Wilson died in 1998 of lung cancer. Brian Wilson rarely performs.

Love, for his part, continues to lead a band legally licensed to call itself the “Beach Boys,” singing songs he helped write 55 years earlier. And carrying just a few grudges. -

A character study of Thomas Jefferson as ‘patriarch’

In “Most Blessed of the Patriarchs,” historians Annette Gordon-Reed and Peter S. Onuf create a character study of Thomas Jefferson, attempting to explain our third president through his perceived role as patriarch to both his families and to his slaves.

‘Most Blessed of the Patriarchs: Thomas Jefferson and the Empire of the Imagination’

by Annette Gordon-Reed and Peter S. Onuf

Liveright, 320 pp., $27.95

It’s not entirely clear that the world actually needs another biography of Thomas Jefferson. True, he played a remarkable role in shaping the young American democracy at a time when it was not at all clear that the rebellious colonies would emerge as a cohesive nation.

He wrote the Declaration of Independence, served as the nation’s third president, second secretary of state and as ambassador to France. But the library of Jefferson biographies is seemingly boundless and includes contributions such as Dumas Malone’s six-volume series (“Jefferson and His Time”), a work that took more than 30 years to complete and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1975 for the first five volumes. What’s more to add?

But perhaps the sheer volume of scholarship is a testament to Jefferson’s enduring contributions and his elusive and contradictory personal life. Jefferson was a master of soaring rhetoric, articulating lofty principles of universal justice and equality while simultaneously not only owning large numbers of African-American slaves, but sleeping with one of them — Sally Hemings — and fathering several children by her. The relationship, long rumored and the subject of fierce debate, is no longer subject to serious question in the wake of definitive DNA testing.

Annette Gordon-Reed and Peter S. Onuf take on the task of explaining Jefferson’s own vision of himself and how he reconciled these conflicting threads in their somewhat awkwardly titled new book, “Most Blessed of the Patriarchs: Thomas Jefferson and the Empire of the Imagination.” Gordon-Reed, a professor at Harvard Law School, is the author of the “The Hemingses of Monticello,” for which she won both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize. Onuf, one of the nation’s leading Jefferson scholars, teaches at the University of Virginia, founded by Jefferson himself. No insignificant pool of talent here.

The book is largely a character study, organized in sections seeking to explain Jefferson’s understanding of himself and his life through his roles as a “patriarch” or as a “traveller,” both at home and abroad.

It’s an approach that allows exploration of Jefferson, unleashed from a chronological narrative. But perhaps more interesting, the book returns, like a touchstone, to remind the reader that Monticello and all that it stood for was built on the backs of enslaved African-Americans. Jefferson may have preferred to turn his face and avoid the harsh reality of his slaveholding, but neither these authors, nor history, will allow that contradiction to stand unexamined.

Of course, Jefferson’s fraught relationship with Sally Hemings is central to understanding Jefferson. Hemings was just 16 when she accompanied Jefferson’s young daughter from Philadelphia to Paris, where he served as the American representative to France.

Jefferson fathered several children with Hemings and, as Gordon-Reed and Onuf note, he held great affection for both his acknowledged as well as his unacknowledged family. He agreed with Hemings to free their children when they reached adulthood, a deal he honored (even as he simultaneously refused to free the slaves who kept Monticello afloat economically).

In the end, the book is an important contribution to understanding Jefferson in light of his now-confirmed relationship with Hemings. Sex, as they say, changes everything. Even our understanding of Jefferson himself. -

‘Seattle Justice:’ crooked cops and payoffs in the Jet City

In “Seattle Justice,” author and former prosecutor Christopher T. Bayley tells the engrossing true story of an era of rampant corruption in the Seattle Police Department.

‘Seattle Justice: The Rise and Fall of the Police Payoff System in Seattle’

by Christopher T. Bayley

Sasquatch, 240 pp., $24.95

Seattle has a reputation for clean government, fairness (to the point of near-dysfunction), and progressive politics. Municipal corruption, seedy cops and crooked prosecutors taking payoffs are things that, in our collective memory, happen in decaying East Coast cities. But not so long ago, right here on the shores of Puget Sound, the Seattle Police built a payoff system equal to the worst of any East Coast protection racket. It all came crashing to a stop through the efforts of a band of young progressive lawyers, intent on challenging the system. And, implausibly, they won.

Christopher Bayley, in his new book “Seattle Justice,” tells the engrossing story from street level up. Seattle, over the course of 100 years, developed an ornate system of tolerating illegal gambling, unlicensed bars and prostitution, all in exchange for cash payments from illegal establishments to crooked police. The payoffs were passed along up the chain to the highest levels of the police department.

Then-King County Prosecutor Charles O. Carroll was a 22-year incumbent, deeply entrenched and utterly uninterested in challenging the system or even questioning it. Carroll dominated Republican party politics and in the 1950s and 1960s was considered by some to be the most powerful man in Seattle and King County. The story of his fall and the collapse of the payoff system is as fascinating as it is surprising to modern ears.

Bayley tells the story with historical context and a fine eye for detail. But, of course, he should know. Bayley himself took on Carroll in the Republican primary in 1970 and not only defeated him but promptly indicted him, and numerous others. Bayley was aided by a rising group of young progressive Republicans (yes, there used to be such a thing as a “progressive Republican” in Seattle, now an endangered species, listed just below the spotted owl) including Tom Alberg, Norm Maleng, Cam Hall, Bruce Chapman, Sam Reed, then-Governor Dan Evans and newly-elected Attorney General Slade Gorton.

Bayley mounted an impressive campaign, winning first the Republican nomination and then defeating Lem Howell, the Democratic candidate. It didn’t hurt that the Seattle Post-Intelligencer managed to tail and photograph Carroll secretly meeting with Ben Cichy, the so-called “Pinball King” who operated the Far West Novelty Company. Far West held the county’s sole license to lease pinball machines, which raked in millions. The photograph of the two men meeting in a darkened car, published on the paper’s front page, shocked the city.

After winning the election, Bayley promptly shut down the payoff system and launched a widespread investigation and series of prosecutions. Although he had limited success in obtaining convictions, he turned a page in Seattle history by definitively ending the payoff system and transforming the County Prosecutor’s office from a place of corrupt partisan cronyism to what it is today: a widely admired model of integrity and competence.

Seattle’s modern police department is, at the risk of stating the obvious, hardly perfect. Police beatings, shootings and violence, particularly against minority members of the community, have not only outraged the city but appropriately brought federal oversight. But one problem it doesn’t have is a citywide protection racket and payoff scheme.

Bayley’s short first-person history is a compelling read and a vivid reminder that Seattle wasn’t always the sparkling technological machine that it is now. In fact, not so long ago, it was something quite different. -

George Mitchell’s ‘The Negotiator’: a peacemaker’s life

“The Negotiator,” a memoir by former U.S. Senator George Mitchell, is less a full autobiography than a collection of vignettes from the life of a man with a tower of accomplishments.

‘The Negotiator: Reflections on an American Life’

by George Mitchell

Simon & Schuster, 304 pp., $27

George Mitchell had a remarkable career: lawyer, U.S. Attorney, federal judge, U.S. Senator, Majority Leader in the U.S. Senate and ultimately a special envoy who successfully brokered peace in Ireland after 800 years of conflict. There are few public figures who could even come close to matching that record.

In “The Negotiator,” Mitchell tells stories from his long career. It’s not really a comprehensive autobiography but more of a series of short, mostly self-congratulatory, vignettes. That’s interesting, to be sure, but disappointing at the same time. With a career like this, Mitchell could have provided a far more substantive history of his public service. This is more amuse-bouche than main course.

Mitchell was the fourth of five children. His mother was a Lebanese immigrant; his father an orphaned son of Irish immigrants. He was raised in small-town Maine, and his love of the state and its people shines through these pages.

Mitchell worked for U.S. Senator Edmund Muskie, where he learned politics from a master of the craft. He briefly served as the U.S. Attorney for Maine in the Carter administration before being named to the federal bench by President Carter, at Senator Muskie’s recommendation.

He didn’t serve long in that position. Senator Muskie resigned from the Senate to serve as President Carter’s Secretary of State, opening up a seat in the Senate. Joe Brennan, then the Governor of Maine, appointed Mitchell to the seat in 1980. He served for 15 years, the last six as Majority Leader.

Mitchell’s Senate actually worked to get things done. Senators from opposite parties felt obligated to work together, to compromise even strongly held positions, in order to accomplish things. It’s a far cry from today’s U.S. Senate, largely shut down from accomplishing much of anything significant by partisan bickering.

His inside stories are at times compelling. He fought a bitter dispute with Senator Robert Byrd over amendments to the Clean Air Act, ultimately winning an amendment to strengthen its provisions. The next day, Byrd, then the Chair of the powerful Appropriations Committee, obtained the tally sheet of votes, “had it framed, and hung it next to the door leading into his Appropriations Committee office. For years thereafter anyone who entered his office was reminded of that vote.”

Mitchell left the Senate in 1995 but he was hardly finished. Joining the board of directors of the Walt Disney Corporation, he rose to become Chairman of the Board. He was appointed by President Clinton to serve as a special envoy to Ireland and, over the course of five long years, helped to negotiate the “Good Friday Accords” that achieved a lasting peace in Ireland. He served, as well, as a special envoy to the Middle East during the Obama administration, where he tried but failed to negotiate peace between Israel, the Palestinians and others in the region.

One of the most hotly debated issues in the Senate today is immigration reform. George Mitchell’s story, a son of immigrants on both sides, provides eloquent testimony to the power of the American dream and the strength — not weakness — that immigration has always provided the United States. His story is worth reading for that reason alone. -

‘Weed the People’: The highs and lows of legal marijuana

In “Weed the People,” Bainbridge Island author Bruce Barcott delivers a thorough and entertaining survey of the burgeoning legalization of marijuana in the U.S. Barcott appears April 15 at Seattle’s Elliott Bay Book Co

‘Weed the People: The Future of Legal Marijuana in America’

by Bruce Barcott

Time, Inc., 400 pp., $22.95

Every year between 2005 and 2010, nearly 800,000 Americans were arrested on marijuana charges, most of them for possessing small amounts of marijuana. That was a threefold increase since the early 1990s. Those arrested and incarcerated were overwhelmingly black or Hispanic, and poor. By 2012, the United States imprisoned a greater percentage of its black population than South Africa did at the height of apartheid. Louisiana’s rate of incarceration is five times as large as Iran’s.

Whatever else one might think of the virtues, or dangers, of marijuana, the rate and scale at which we have imprisoned young black and Hispanic men for its possession is nothing short of an outrage.

In “Weed the People,” Bainbridge Island author Bruce Barcott (“The Last Flight of the Scarlet Macaw,” “The Measure of a Mountain”), surveys the remarkable transformation of marijuana from an outlawed illegal drug to a legalized adult intoxicant in several states. It’s an outstanding review of the history of marijuana regulation, the remarkable political history of its decriminalization, and its rapidly unfolding impact on modern life.

The regulation of marijuana has a long and tortured history. Marijuana was treated as a relatively minor nuisance until it was banned in 1937 and later scheduled as a dangerous drug under the Controlled Substances Act. With the proliferation of tough mandatory sentencing schemes, marijuana became the gateway drug to long-term prison sentences and the imprisonment of a generation of young men and women.

Barcott traces the roots of the medical marijuana movement from the ravaged gay communities suffering from AIDS to widespread acceptance of the benefits of marijuana for those suffering from cancer, AIDS and a variety of other illnesses. But it took serious political organizing efforts to move marijuana from a fringe alternative therapy to open legalization. Alison Holcomb, a lawyer working with the ACLU of Washington, provided that push.

Barcott is no cheerleader for legalized pot. He takes a hard look at serious questions about the link between marijuana and schizophrenia, the hazards of ingesting THC, the active ingredient in pot, by smoking it, and its rather dramatic demotivating effect. But the statistics on public health are compelling: 440,000 Americans die each year from cigarettes; 46,000 die from alcohol-related causes; 17,000 die from prescription drug overdoses. There are no reported deaths from marijuana overdose. Zero.

Barcott spends the bulk of the book interviewing and profiling the curious business community that has exploded in Washington and Colorado, rushing to fill the demand and seeing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to establish leading brands in an emerging and highly lucrative trade. The contrast between Harvard-trained private equity business operatives and their more rustic Grateful Dead-listening predecessors is hilarious.

Marijuana is now “legal” in Washington and Colorado. Voters in Alaska, Oregon and Washington, D.C., have similarly voted to legalize marijuana. California appears poised for similar reform. But pot remains illegal under federal law everywhere, and it’s only through the forbearance of federal law enforcement officers that these state-level experiments have been allowed to proceed.

As its playful title suggests, Barcott’s writing is casual and breezy, perhaps befitting his subject, but jarring at times. But it’s a study long overdue, and Barcott thoughtfully examines the coming social revolution. Marijuana stores now openly operate in Washington and Colorado. Skiers visiting Colorado’s resorts routinely stop along the way to stock up. Professionals used to send bottles of wine to clients as a thank you for their patronage. Will little vials of high quality pot be next? -

‘Napoleon’: supreme strategist in governing, love and war

Andrew Roberts’ spectacular new biography, “Napoleon: A Life” shows how Napoleon Bonaparte won his battles, engineered his own political ascent and left an enduring imprint on the modern world.

‘Napoleon: A Life’

by Andrew Roberts

Viking, 926 pp., $45

Napoleon Bonaparte, France’s early 19th century self-declared “emperor” was certainly extraordinary. But whether he was an extraordinarily talented executive who laid the foundations of modern France (and beyond) or an extraordinarily egotistic despot responsible for death and destruction on a scale almost unmatched in European history (until the rise of Nazi Germany) is a debate that continues to flourish to this day.

Andrew Roberts’ “Napoleon: A Life” is a stunning 920-page overview of Napoleon’s rise and almost as dramatic fall. Although there surely are as many biographies of Napoleon as years since his death, Roberts is the first biographer to utilize the recent publication of Napoleon’s 33,000 surviving letters. His careful scholarship is breathtaking. He researched the book in 69 archives, libraries and museums in 15 countries and personally walked 53 of Napoleon’s 60 battlefields. That meticulous research pays off in a fascinating study of Napoleon’s contributions to the modern world (for better or worse).

Born on Aug. 15, 1769, in Ajaccio, Corsica, Napoleon won a royal scholarship to a military school in France and ultimately was commissioned into an artillery regiment in 1785. He embraced the French Revolution and won recognition by recapturing Toulon from French Royalists. He rose quickly through the military ranks, ultimately taking command (at 26 years old) of the French Army of Italy against the Austrians, crushing them with a brilliant display of strategic deployment of his forces.

He led the French invasion of Egypt and, aided by a decidedly one-sided propaganda campaign, returned to Paris to a thunderous hero’s welcome. With unmatched political finesse, he engineered a coup that installed him as one of three members of the ruling Consulate, then as First Counsel, and ultimately as Emperor.

Along the way he married Josephine de Beauharnais, the widow of a guillotined royalist. She was older, far more sexually experienced, and neither loyal nor discreet. But Napoleon adored her anyway and forgave her, even after he discovered her numerous affairs. Napoleon enjoyed the company of more than 22 mistresses, so he hardly had grounds to complain.

Napoleon’s staggering impact on the modern world is difficult to overstate. As Roberts notes, “the ideas that underpin our modern world — meritocracy, equality before the law, property rights, religious toleration, modern secular education, sound finances and so on — were championed, consolidated, codified and geographically extended by Napoleon.” He rationalized local government administration, encouraged science and the arts, abolished feudalism and codified the law.

But above all, Napoleon was a warrior. Although often criticized for his boundless ambition and ego, war was declared on him far more often that he declared war on others. His military campaigns and strategy are studied to this day. His decision to invade Russia in 1812 was a fatal mistake, but hardly irrational. The French had defeated the Russians three times between 1799 and 1812, he had fought and won in blizzard conditions, and had won battles at the far end of long lines of communications at Austerlitz and Friedland. But he lost 400,000 of his men in Russia, more than 100,000 of them from a typhus epidemic. It was the sheer size and ferocity of his army that led the Russians to strategically retreat, avoiding battle and drawing Napoleon and his army ever deeper into the Russian heartland — and winter.

This book is simply spectacular. Roberts writes beautifully and, aided by meticulous historical research, brings Napoleon alive before the reader, with grapeshot and cannon fire splattering across the page.

Napoleon never lacked confidence. After his defeat at Waterloo and banishment to St. Helena, he was asked why he had not taken Frederick the Great’s sword when he was in Russia. He replied, “Because I had my own.” -

‘Indonesia Etc.’: an island nation of remarkable contrasts

Elizabeth Pisani’s book “Indonesia Etc.” is a personal tour of a country of extremes, from the urban hive of Jakarta to the remotest of the country’s 13,500 islands, where people still live without electricity or water.

‘Indonesia Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation’

by Elizabeth Pisani

W.W. Norton

304 pp., $26.95

Indonesia is perhaps the most overlooked country in the world. When it declared independence in 1945, it famously declared that it would “work out the details of the transfer of power, etc. as soon as possible.” It’s been working on that “etc.” ever since.

In “Indonesia Etc.,” Elizabeth Pisani takes us on a very personal tour of the world’s fourth most populous country. Pisani lived and worked in Indonesia as a journalist, and then later as an HIV epidemiologist. But to write this book, she took 13 months off and traveled 26,000 miles throughout the 13,500 islands that make up Indonesia, living with locals and traveling by every conceivable means of transportation, from overloaded commercial ships to rickety buses following their own schedule.

Indonesia is a study in remarkable contrasts. Jakarta, its capital on the island of Java, could not be more different from its far-flung islands. It was home to 600,000 people at independence and has grown 17 fold since that time, now hosting more than 28 million — the second largest urban center in the world behind Tokyo. Jakarta tweets more than any other city on Earth. Yet 40 percent of the city is below sea level and the entire city floods every year.

By contrast, more than 80 million more remote Indonesians live without electricity or water. The island nation is home to more than 300 ethnic groups, many with strong independent traditions and little contact with the slick amenities of modern life. Although Indonesia is the largest country in the world to consist entirely of islands, the Word Economic Forum ranked its port infrastructure 104 out of 139 countries. And that’s only the start of a massively crumbling or insufficient infrastructure and a government structure riddled with corruption and inefficiency.

Indonesia was a Dutch colony, but declared its independence after liberation from the Japanese occupation during the war. Sukarno, Indonesia’s founding president, balanced the military against the Communist Party of Indonesia, but ultimately lost control after an attempted coup was violently crushed by the army and General Suharto seized control. He ruled the country until his resignation in 1998.

Indonesia’s far-flung islands host a remarkably diverse range of subcultures, languages and ethnic religions. But in each, although an utter stranger, Pisani was warmly greeted and made to feel at home, often invited to stay with the family of whomever she happened to meet on the ramshackle bus or crowded boat deck.

Pisani does an excellent job of describing her travels with colorful detail and interesting stories. Her first-person focus, with interesting statistics thrown in for good measure, ultimately limits her book’s potential. Like a long letter home, “Indonesia Etc.” gives you an excellent sense of how Ms. Pisani spent her year abroad, but one is left longing for a larger focus on this unique country.

Maybe that’s precisely because Indonesia is so elusive, even after 13 months’ study. Looking back on her year, she observes that “I waited for boats that were eighteen hours late with little more than a shrug … When I did ask questions, I often settled quickly for the most common answer: Begitulah. ‘That’s just the way it is.’ Over time, I grew to accept that there is a very great deal about Indonesia, the world and life in general that I will just never know.” -

‘A Court of One’: Judge Scalia, sociable friend, formidable foe

Bruce Allen Murphy’s biography of U.S. Supreme Court judge Antonin Scalia, “Scalia: A Court of One,” brought back memories for Seattle lawyer Kevin J. Hamilton.

Bruce Allen Murphy

Simon & Schuster

644 pp., $35

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. once said that “the longing for certainty … is in every human mind. But certainty is generally illusion.” Justice Antonin Scalia would assuredly disagree. Certainty is, and always has been, his defining characteristic.

Justice Scalia has been on the Supreme Court since 1986. Over nearly three decades, he has confronted a variety of difficult decisions, but rarely has admitted uncertainty as to the outcome. As he likes to say, “anyway, that’s my opinion. And it happens to be right.” In “Scalia: A Court of One,”(Simon & Schuster, 644 pp., $35) Bruce Allen Murphy, a Lafayette College professor, provides a compelling biography of one of the most conservative, combative, and bombastic Supreme Court Justices in our nation’s history.

In 1985, then Judge Scalia served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, generally regarded as the second most powerful federal court in the nation. It was, at the time, closely divided between liberals and conservatives. Aside from Judge Scalia, it featured Judge Robert Bork (who lost his own confirmation battle to the Supreme Court just a few years later), Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg (later appointed to the Supreme Court), and Judge Kenneth Starr (later the infamous prosecutor in the Monica Lewinsky trial). On the left, Judge J. Skelly Wright anchored the liberals, who included Chief Judge Patricia Wald, Spottswood Robinson, and Harry Edwards. Judge Wright had enforced desegregation of the Louisiana schools after Brown v. Board of Education and had been appointed to the D.C. Circuit by President Kennedy. Protesters burned crosses in his yard to protest his opinions.

I clerked for Judge Wright in 1985 and, from that vantage point, watched as Judge Scalia worked his personal charm on a closely divided court. It was overture, as it turned out, for the larger opera to come.

Two seemingly inconsistent traits defined Judge Scalia. First, he was, and remains, one of the best writers on the Court. His opinions, whether read in disgust by his detractors or embraced as well reasoned truth by his supporters, are always entertaining. Second, he is gregarious almost to a fault.

On the D.C. Circuit, he wielded both weapons to advantage. Judge Scalia would frequently socialize with the swing members of the court. His easy demeanor, quick laugh, and razor-sharp arguments often pulled wavering judges to his side.

He dominated oral argument, showering the lawyers with difficult, and sometimes impossible, questions. Lawyers gripped the podium in panic and often left the courtroom shaken.

His writing was even more pointed. Law clerks often write early drafts of court decisions which become the focus for debate by internal memoranda between judges. But debating with Judge Scalia in writing was not for the faint hearted. Years later, as a practicing lawyer, I learned to appreciate his antagonistic writing style, not as a model, but as a bracing lesson in the value of careful writing. Loose ends, one quickly learned, were ammunition for blistering counterattack.

Judge Scalia did not hesitate to ridicule and belittle arguments — or judges — which strayed from his rigidly conservative viewpoint. Judge Scalia promoted an “originalist” theory of constitutional interpretation, seeking to discern the public understanding of the constitution at the time of its ratification. The constitution, he likes to say, is “dead” and means what it meant when adopted. He has nothing but scorn for those who viewed the constitution as a “living” document, changing with contemporary understanding of, for example, “cruel and unusual” punishment.

This style is bracing and hardly one likely to build collegial relationships. Only a year after my clerkship with Judge Wright ended, then-President Reagan nominated Judge Scalia to the Supreme Court. He was easily confirmed. But in that forum, his caustic style has been corrosive. Supreme Court justices have to work together, sometimes over decades. He was, as Murphy calls it, a “court of one” and he lost power struggles to Chief Justice Rehnquist, then to Justice Kennedy, and later to Chief Justice Roberts. But even so, his views have often prevailed in key decisions, including Bush v. Gore.

“A Court of One” is a terrific start to understanding Justice Scalia and his impact on American constitutional law. Murphy, though, is hardly a neutral observer, and his hostility to the justice is transparent. As a result, this biography is likely to be as controversial as its subject. Perhaps that’s inevitable. Certainly Justice Scalia of all people should appreciate strongly held opinions.

Justice Scalia is now in his 80s, but age has neither softened his rough edges nor moderated his views. For those of us who knew him before his Supreme Court appointment, that’s hardly a surprise. -

‘When the United States Spoke French’: Five eminent Frenchmen come to the aid of a young America

François Furstenberg’s new book “When the United States Spoke French” follows the fortunes of five eminent Frenchmen who fled to this country after the French Revolution and aided a young America.

“When the United States Spoke French: Five Refugees Who Shaped a Nation”

by François Furstenberg

Penguin Press, 498 pp., $36

In 1789, inspired in part by the American experiment, the French Revolution rocked Europe. A handful of Frenchmen who led the Revolution in its early days watched in dismay as it devolved into chaos. They escaped across the Atlantic to find refuge in the United States. Quickly integrated into life in Philadelphia, the new capital, they were warmly welcomed by Americans who enthusiastically celebrated the French revolutionary fervor.

In “When the United States Spoke French: Five Refugees Who Shaped A Nation,” (available at booksellers July 14, Bastille Day) Johns Hopkins University history professor François Furstenberg recounts these tumultuous years from the viewpoint of five highly influential Frenchmen: Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (later a foreign minister under Napoleon), the duc de Laincourt, Louis-Marie Vicomte de Noailles, Moreau de Saint-Méry, and Constantin-François Chasseboeuf de Volney.

They were quite the collection. Talleyrand, it was said, “brings with him all the vices of the old regime, without having been able to acquire any of the virtues of the new one.”

At the time, the fledgling United States was crippled with debt, excluded from many ports in the British Empire (particularly in the Caribbean) that had been key trading partners, and had few financial resources to invest in its struggling economy. The French émigrés, with connections to European capital, were able to assist their new hosts in securing lines of credit.

For the Americans, the French were the source of endless fascination. Volney tutored the daughters of William and Anne Bingham, two of the most prominent Philadelphians, in French. Noailles, a former Versailles dancing partner of the French queen, Marie Antoinette, gave them dancing lessons.

At the time, the United States looked to their Revolutionary allies, the French, for support. But it was not to last. In 1794 the United States signed the Jay Treaty with England, signaling neutrality in the war between France and England, which the French considered nothing less than betrayal. An undeclared naval war with France ensued, followed by French efforts to control New Orleans, the key to the vast Mississippi watershed.

Had they succeeded, much of the territory west of the Appalachian Mountains might well have become French. But the army sent to secure French claims stopped first to quash rebellion in French colonial San Dominique (now Haiti), where it suffered grievous losses, mostly from yellow fever. With few options, the French Emperor Napoleon settled for selling the Louisiana Territory to the United States (rather than see it fall into English hands).

The 20-year period covered by the book saw profound changes — for the United States and for France. As Furstenberg notes, “The United States had gone from a small group of states huddled between the Appalachians and the Atlantic coast to a continental power stretching across the Mississippi Valley to the Rocky Mountains.” France had gone from monarchy, to republic and finally to empire. Wars had started, ended, and erupted again.

Furstenberg opens a window into a lost world of glittering Philadelphian dinner parties, rough backwoodsmen speaking French and homesick émigrés. It’s a fascinating portrait of the diplomatic intrigue between France and England for power and position, with the United States displaying a disconcertingly astute aptitude for playing them off against each other.

“When the United States Spoke French” is essential reading for understanding the complex relationship between France and the United States that, to this day, endures.