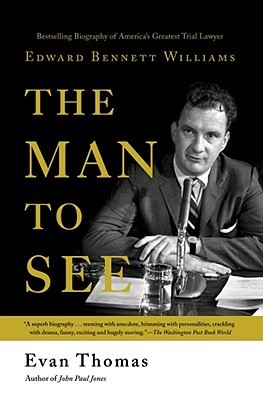

‘The Man to See: Edward Bennett Williams’

by Evan Thomas

Simon & Schuster, $27.50

Edward Bennett Williams, one of the best known trial lawyers of our time, characterized the ideal client as “a rich man who is scared.” Williams had plenty of them: mafia don Frank Costello, former Treasury Secretary and Texas governor John Connally, President Lyndon Johnson, Jimmy Hoffa and the Teamsters Union, the Washington Post – even junk-bond king Michael Milken.

Williams recognized that taking every case to trial was not necessarily the best defense: “Nothing is often a good thing to do and always a brilliant thing to say.” Whether by delaying, cajoling, bargaining, or simply wearing down the prosecution, Williams often got his clients off without even entering the courtroom.

This new biography of Williams, by Newsweek’s Washington Bureau chief Evan Thomas, covers his life and times thoroughly and is a pleasure to read. It is packed with stories of Williams’ notorious trials and lively wheeling and dealing, both in and out of the courtroom, as well as his later fame as owner of the Washington Redskins and Baltimore Orioles. Thomas carefully notes the inconsistencies in Williams’ positions and carefully points out the flaws in the man that many consider the ultimate trial lawyer.

Brendan Sullivan, Williams’ protege, once indignantly defended his right to object in the Senate hearing investigating his client, Oliver North, by declaring, “I am not a potted plant.” It’s a claim Edward Bennett Williams never needed to make.

Month: January 1992

-

‘The Man to See: Edward Bennett Williams’

-

‘Praying for Sheetrock’

‘Praying for Sheetrock’

by Melissa Fay Greene Addison-Wesley, $21.95

“Praying for Sheetrock” is a beautifully written first book by an ambitious young lawyer who set out to change the world 15 years ago by working in a rural Legal Services office in an obscure Georgia backwater: McIntosh County. What Melissa Fay Greene found was an astonishing pocket of the world, seemingly untouched by the civil-rights movement and still controlled by a corrupt white sheriff and his courthouse gang.

Sheriff Poppell did not rule through force, but through patronage. When a truck crashed on the interstate, he would spread the word and stand by quietly while the poor harvested the shoes, candy bars, or whatever unfortunate cargo was lost. He was involved in drug smuggling, prostitution, and gambling, but most of all, he enforced the segregated status quo. Greene details the black community’s awakening and overthrow of the sheriff, assisted in part by Legal Services lawyers.

She tells the story through the eyes and voices of the community, with poetic and striking portraits of the county, its people, and its politics. She could have stopped with a romanticized version, untouched by human weakness, but Greene opts to tell also of the downfall of the most prominent black activist. He succeeded in overthrowing the sheriff and was elected to the County Commission, only to succumb to temptation and be convicted of corruption. It’s messy and inelegant, just like life. That, I suppose, is about the highest praise one can give to a portrait of a community in change.