‘William Clark and the Shaping of the West’

by Landon Y. Jones

Hill and Wang, 394 pp., $25

There are few more revered figures in American history than William Clark and Meriwether Lewis, explorers of the American West. Although Lewis died within three years of his return from the Lewis and Clark expedition, Clark lived a long life in military service to the United States. In “William Clark and the Shaping of the West,” Landon Jones delivers a revealing portrait of Clark’s entire life, not just the famous journey.

Jones, a former managing editor at People magazine and contributor to Life, Time and Money, is on the board of the National Council of the Lewis & Clark Bicentennial. But his fascination for the expedition notwithstanding, Jones’ work is an unflinching and frankly unflattering portrait of a beloved American hero.

Clark was born in 1770 and was raised in a country still struggling with its newfound independence. Joining the American military when he was just 19, Clark served the federal government for several decades, securing outposts in the West, leading men into the wilderness and, above all, fighting the Indians.

Jones’ masterful biography brings to life the gritty and brutal existence of life on the American frontier. Arriving pioneers found fertile land abounded as they pushed westward, but with the land came the Native American tribes who resented the arrival of white settlers, particularly when it was “guaranteed” by earlier treaties that the settlers refrain from further encroachment. The weak national government was unable to control the settlers, who moved far beyond treaty-established boundaries. When the inevitable hostilities arose, it was the Indians who were blamed as “savages” and were attacked by the military – including at times Clark himself – and then guaranteed peace only in exchange for land and resettlement further west.

The story, familiar as it is, is difficult to read without disgust. Jones’ narrative is superb at bringing the conflict to life: American soldiers digging up Indian corpses to scalp or burn them, pregnant Indian women hung and mutilated, and enormous fields of Indian corn burned to starve the tribes into submission (the same tactic used by the British during the Revolutionary War and decried as “barbaric” by the colonies). While Jones does not attribute any of these incidents to Clark himself, Clark plainly was deeply involved in the conflict throughout his military career and could not have been unaware of them. To modern Americans, it seems almost absurd to question that the young United States would bridge the continent. But, from Clark’s perspective, the outcome was far from certain. French, English and Spanish armies maneuvered and manipulated Native American tribes, shifting alliances to balance power in the unsettled West.

Clark was 33 years old when he was invited by Meriwether Lewis to join him on an expedition to explore the Western interior. The Lewis and Clark expedition has been the subject of scores of books, but Jones manages to cover it in a brisk 30 pages, drawing heavily from the expedition’s journals and correspondence.

Upon his return from the expedition, Clark married 15-year-old Julia Hancock, was appointed principal Indian agent for the U.S. government and settled in the former French city of St. Louis. In his remaining years, Clark acted as the federal representative in negotiating countless treaties with vanishing Native American tribes as they were pushed inexorably westward and toward oblivion.

In 1831, a band of Sauks attempted to return to their tribal homeland on the east bank of the Mississippi in what is now Illinois. As the conflict escalated, the Sauks tried to escape back west but, unable to negotiate peace terms because the pursuing Americans had no interpreters, the Sauks “put up little resistance, as most were attempting to find shelter or help the women and children scramble across the river’s mud flats and small islands. … The carnage was terrible; men, women, and children were shot indiscriminately, and their blood-streaked bodies floated downriver.”

The few who escaped were hunted and killed. Clark – at the time the Indian superintendent for the West – was delighted to hear the “glorious news.”

Clark died in 1838 at age 68. He outlived Lewis by more than 29 years. By the time of his death, Clark had personally signed 37 separate Indian treaties, more than anyone in American history, and supervised the removal of 81,282 Indians from the East. As Clark lay dying, the U.S. Army began moving the 17,000 Cherokee Indians west, on a thousand-mile forced march known as the “Trail of Tears.” Four thousand of them died. It was the culmination of a process started, facilitated and enforced by William Clark.

Clark’s many contributions, including the Lewis and Clark expedition itself, will not soon be forgotten. But this thoughtful biography suggests that Clark’s entire life was a more complex, and decidedly less heroic, affair.

Blog

-

New biography of William Clark exposes his involvement in the displacement of Native Americans

-

A formidable woman and diplomat

President Clinton visited Seattle a couple of years ago after leaving the White House, and he addressed an overflow lunch crowd jamming the Westin Ballroom. As he surveyed the world’s troubles and how America should respond, the contrast between his approach and that of the new Bush administration could not have been more stark. Reading former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright’s just-published memoirs, “Madam Secretary” (Miramax, $27.95), brings much the same thought to mind – how far we’ve traveled from working with NATO and the U.N. to address Bosnia and Kosovo, to working around our closest NATO allies and the U.N. to address Iraq.

Madeleine Albright’s life could hardly have been more interesting. Her father was a Czech diplomat and, when the Nazis invaded, Albright’s family escaped on a night train out of Prague. Her father worked in London with exiled Czech President Edvard Bene{scaron}, and then in Prague after the war, until the Communists ousted the democratically-elected leadership. Albright’s father secured a posting to the United Nations in New York, representing Czechoslovakia, but worked behind the scenes to secure refugee status.

After leaving government service, Albright’s father took up teaching, and the family resettled into suburban American life. Madeleine met her future husband, Joe Albright, at Wellesley College, and her marriage brought her wealth (his uncle was Harry Guggenheim) and powerful family connections. Albright became an American citizen, raised three children and simultaneously secured her Ph.D. from Columbia University’s prestigious Russian Institute.

With her degree, Albright worked for U.S. Sen. Edmund Muskie and was later invited to join the staff of the National Security Council by her former college professor Zbigniew Brzezinski (who had been selected to be President Carter’s national security adviser). With President Carter’s defeat in 1980, Albright returned to academia and worked on successive presidential campaigns.

When President Clinton was elected, Albright served first as the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and, in the second term, as secretary of state. Shortly after her confirmation, news stories surfaced revealing Albright’s Jewish ancestry. Albright achingly writes of her heartbreak at discovering the fate of three of her grandparents in Nazi concentration camps, their names etched in the wall of a synagogue in Prague that she had visited.

Albright’s writing is smooth, captivating and thoughtful. The book provides a sweeping overview of foreign crises during the entire eight-year term of the Clinton presidency, with fascinating behind-the-scenes glimpses into personal encounters with world leaders from across the globe. From Iraq to Bosnia, the tangle of Middle East politics, the slaughter in Kosovo, her management of the relationships with NATO allies, and her visit to North Korea, her story is a short course in near-term world history. Much of it is familiar, but it’s refreshing to review how differently America responded to international challenges just a few short years ago: Albright sought to contain the Iraqi threat with international sanctions and inspections rather than outright war. She responded to North Korea’s nuclear ambitions with containment and engagement. And she used NATO air strikes – working with then-NATO Supreme Allied Commander Wesley Clark – to bring Slobodan Milosevic to justice when many said that air strikes alone would never resolve the issue.

But far more interesting are Albright’s personal reflections on her appointment as the highest-ranking woman ever to serve in the U.S. government. Her insights into the unique challenges posed to a woman serving in a largely male environment are entertaining. At the end of one dinner, for example, she realized that she had spilled some salad dressing on her skirt – a spill that would never have been noticed on a man’s dark suit. For the after-dinner group photo, she turned the skirt around to conceal the stain. She dryly comments: “Not a move with which Henry Kissinger could have gotten away.”

But, for all its thoughtful discussion of foreign relations and international intrigue, the book is surprisingly silent about the single most defining event of the Clinton presidency: his impeachment and trial before the Senate. Albright devotes a handful of paragraphs to the scandal and mentions in passing the president’s apology to his cabinet for misleading them. But future historians will be left wondering about the impact of the impeachment and trial of a sitting president on the foreign relations of the country.

Even with this rather dramatic omission, Albright’s memoirs are a fascinating review of recent American history, a compelling insight into foreign relations up close and personal, and a stirring reminder of the power of diplomacy in achieving peace in a troubled world. -

A historian makes a case for imperialism

‘Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power’

by Niall Ferguson

Basic Books, $35

At its height, the British Empire governed nearly a quarter of the world’s population and dominated every ocean on Earth, all from a relatively tiny set of rain-swept islands off the coast of Europe. The British, so goes conventional thinking, settled – and then lost – its American colonies, ruled India, established a prison population in Australia, mapped the depths of Africa and played a key role in perpetuating slavery. The British Empire disintegrated after World War II, unable to muster the will or cash to fund the enterprise, and is now commonly viewed as an anti-democratic exploiter of Third World colonies, one that left ruin in its wake.

In “Empire,” British upstart historian Niall Ferguson begs to differ. Ferguson argues that the British Empire in fact offered incalculable benefits to the world and to its colonies. Ferguson, a Research Fellow at Oxford and a New York University professor, makes no apologies for challenging the politically correct view of the British Empire.

At the outset, Ferguson acknowledges the British Empire’s sins but argues that it in fact exported a great deal that was worthwhile. Democratic principles, the free flow of capital, labor and technology, and stable governments all followed British colonialization. Ferguson argues that British interference with local customs was sometimes warranted, even if imposed from without. Widow burning in India, he writes, should have been outlawed, even if it was a long-settled part of local practice.

In 350 pages, richly illustrated with tables, graphs and maps, Ferguson provides a whirlwind historical tour of the . From English slave traders to South African revolts, from David Livingston’s bushwhacking in Africa to the ungrateful American colonies, he provides a fascinating short course on colonial history complete with pith helmets, red coats and stiff upper lips.

The British imposed a system of government on its colonies that protected private property, imposed a functioning legal system, and provided stable and honest government, allowing the countries to develop within a framework that scarcely would have been possible without direct British intervention. Countries that were once British colonies had a significantly better chance of achieving enduring democratization after independence than those ruled by other countries or left to their own fate.

Ferguson argues that the evidence simply overwhelms any contention that the British Empire impoverished its colonies. In fact, he argues, although many former colonies remain desperately poor, the real disparity has only emerged since they achieved independence from Britain. And the list of the world’s stable democracies reads like a virtual catalog of former British colonies: the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and India, just to name a few.

Ferguson’s writing is engaging, thought-provoking and – at times – frankly outrageous. His condensed history is a challenge to the United States, reminiscent of one issued more than 100 years ago by Rudyard Kipling on the occasion of the Philippine-American war, a demand to the U.S. to shoulder its imperial responsibilities (in rather famously inappropriate language): “Take up the White Man’s Burden, And reap his old reward; The blame of those ye better, the hate of those ye guard… “

Like it or not, he argues, the United States stands alone in the world as a superpower. The United States today is vastly wealthier relative to the rest of the world than Britain ever was; the U.S. economy is larger than that of the next four nations (Japan, Germany, France and Britain) combined. American power already makes it an empire whether it wants the role or not. The American problem, he argues, is its own reluctance to export its people, capital and culture throughout the world to those “backward regions” where, he argues, it is desperately needed and, if ignored, will breed the greatest threats to global security.

Although carefully argued in scholarly prose, Ferguson’s point could hardly be more inflammatory in a world embittered by American unilateral action in Iraq. Most of the European Union, a large segment of the American population and virtually all of the Arab world are rather unlikely to conclude that the world needs more aggressive American intervention rather than less.

And Ferguson fails to address a key point in the debate over America’s foreign policy: whether American power is best exercised through the international institutions that the United States itself created and nurtured through the postwar era or through unilateral military action.

That’s the real argument that today has engaged editorial pages from Paris to Washington, is likely to define the coming election and will shape the coming era as it unfolds. Unfortunately Ferguson, in his rush to draw lessons for the Americans in how to run the world like the British once did, overlooks that debate altogether. -

Wild Bill’ rides again: A life of Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas

‘Wild Bill: The Legend and Life of William O. Douglas’

by Bruce Allen Murphy

Random House, $35

William O. Douglas served on the U.S. Supreme Court for 36 years, longer than any other justice in American history. He wrote the most opinions for the court, issued the most dissents, wrote more books, married more women, endured more divorces and was threatened with impeachment more often than any other justice before or since. Douglas left a legacy that is difficult to imagine, let alone catalog.

Bruce Allen Murphy’s magnificent new biography, “Wild Bill: The Legend and Life of William O. Douglas,” rises to the formidable challenge posed to anyone who would attempt the task. Fifteen years in the making, it is the first truly comprehensive biography of the justice – and one well worth waiting for.

Douglas’ life, as he told it, was a stirring victory against the odds. According to Douglas, he suffered polio as a child and regained his ability to walk only through the dedication of his mother and his own steel-eyed grit in hiking the Yakima foothills. He claimed to have been raised in a poor family, to have ridden the rails east to law school at Yale, to have served in World War I, and to have graduated second in his class from law school.

Unfortunately, much of the story isn’t exactly accurate, as Murphy’s biography points out, backed up by hundreds of interviews and a close review of voluminous papers only recently made public.

Douglas did suffer a mysterious illness as a child, but it was never diagnosed as polio then or later. Douglas’ early years in Yakima were challenging, but his widowed mother was hardly destitute. He did ride a “sheep train” to law school, but it was a comfortable passage and hardly counts as riding the rails. Douglas served his country well and long on the court, but he never served in the military, apart from a few weeks of volunteer service in the Students’ Army Training Corps. And, brilliant as he was, he was not second in his class at Yale Law School.

And the sad part is this: None of this myth-making is necessary to recognize Douglas’ extraordinary achievements. Douglas was plainly a brilliant man who succeeded against daunting odds, rising from an obscure (if not entirely poor) upbringing in Yakima. He gained fame teaching at Yale Law School and was appointed by then-President Franklin Roosevelt to the Securities and Exchange Commission. Widely praised by New Deal liberals for his dramatic work in challenging securities fraud, he became an FDR favorite, playing a regular game of poker with the president. Twice he was nearly nominated for the vice presidency. His record hardly needs exaggeration.

He was barely more than 40 years old when he was appointed to the Supreme Court. His service on the court was remarkable by any measure, and his opinions and dissents identified issues that even today continue to resonate – the right to privacy (and later abortion) was founded almost entirely on Douglas’ reasoning in early cases. He broke ground in environmental cases, in free-speech cases, and in search-and-seizure cases. But he chaffed on the court, never entirely happy to be so far from the fray, and frustrated that his hidden presidential ambitions had never been satisfied.

Although Douglas gained fame on the East Coast, he always considered Yakima his true home. He spent his summers at his Goose Prairie cabin, roaming far and wide among his beloved Cascade Mountains. Douglas held hearings in the Yakima County courthouse and once even heard out lawyers with an emergency petition beside a campfire at a high-mountain camp (making them return the following day for the ruling). His spirit still roams the Cascades, with his name often inscribed in trail registers by hikers as an informal tribute to “The Judge.”

Despite his remarkable professional achievements, Douglas’ personal life was a disaster. Douglas had two children to whom he was a cold and distant father. Worse, he relentlessly cheated on his wife and chased women constantly, which ultimately led to his first divorce. He married and divorced two other women before his fourth, and last, marriage to Cathy Douglas. She was 23 and he was 67, leading one Goose Prairie observer to comment that the justice just might have “overstocked his pasture this time.” He was also brutal on his office staff, famous for his harsh criticism of their work.

Douglas was threatened with impeachment four times, most seriously by President Nixon. Informed by the attorney general of the impending impeachment effort, Douglas responded: “Well, Mr. Attorney General, you’d better saddle your horses.” Both efforts ended in failure.

Even trimmed down to a more historically accurate portrait, William O. Douglas’ accomplishments were staggering. “Wild Bill” is an outstanding review of Douglas’ life, legacy, and legend. It’s likely to remain the definitive Douglas biography for years to come and is, indeed, a fitting tribute to Washington’s most famous son. -

Grisham’s ‘The King of Torts’ action-packed but thin on plot

‘The King of Torts’

by John Grisham

Doubleday, $27.95

After venturing into other forms of fiction, John Grisham returned to the courtroom with last year’s thriller, “The Summons.” He re-enters the fray with his latest courtroom thriller, “The King of Torts.”

In his new novel, Grisham takes on the sleazy world of mass-tort lawyers who specialize in suing large corporations in enormous class-action lawsuits, securing huge fees in return for relatively small recoveries for their clients. “The King of Torts” offers everything one expects from Grisham: fast and suspenseful action, a thin and extremely implausible plot and a stunningly predictable conclusion.

Clay Carter is an overworked, underpaid public defender in Washington, D.C., representing a motley collection of junkies, repeat offenders and violent criminals. Stuffed in a dismal, cramped office, he is burned out and disheartened. When his longtime girlfriend walks out on him, egged on by her preening and socially ambitious parents, Carter finds himself at the end of his rope. But suddenly, as so often seems to happen in Grisham novels, a well-dressed stranger appears, offering Carter a deal too good to resist. Max Pace is a legal “fireman” hired by big corporations to deal with potential legal troubles before they explode. Pace’s client is a big pharmaceutical company whose drug experiments went dangerously awry, leading to a string of deaths. The offer? Represent the victims, broker quiet settlements and releases, and earn a fee of $15 million in return.

Carter wrestles with the decision, but ultimately accepts the offer. He quits his job, recruits several colleagues, and opens shop in a posh law office set up by Pace virtually overnight. Bankrolled by the $15 million windfall, Carter gets down to work quickly.

With Pace providing a series of inside tips, Carter files a series of mass-tort suits, using expensive nationwide television advertising to drum up thousands of clients. He is soon hailed as the “King of Torts,” a boy wonder of the mass-tort bar, and is initiated into the small network of big shot, self-proclaimed fighters for the underdogs.

At first repulsed at his colleagues, who seem more interested in buying the biggest jet, the fanciest sports car or the most palatial mountain retreat, Carter’s resistance is slowly overcome as he slips ever deeper into the lifestyle of the rich and ostentatious mass-tort lawyer. Along the way, he engages in blatant insider trading in the stocks of the corporations he is suing, betrays virtually all of his clients and their interests, files lawsuits with little or no evidence to support them, and accepts advice from and invests millions on the word of people he barely knows. The ethical violations and assorted criminal behavior in just the first 100 pages would make an outstanding law-school ethics exam.

Of course, the entire plot strains the patience of even the most credulous readers. Why would a lawyer, who has heretofore suffered on a public-defender salary (despite a sparkling law-school career at Georgetown Law School) in the interests of the public good, abandon everything on the improbable word of an unknown stranger and suddenly launch himself on a whirlwind of shady deals and ethical violations? Why would a “fireman” like Pace risk disclosure by involving unknown lawyers and particularly obscure criminal lawyers who, of all people, know better than most the costs of shady deals? And what corporation – no matter how deranged – would risk this sort of open manipulation of the civil-justice system? Far from helping to insulate the company, such tactics would enormously magnify the problem and expose those involved to serious criminal charges.

Class-action litigation in the United States is certainly long overdue for reform, and Grisham’s portrayal of self-righteous and hypocritical leaders of the mass-tort bar, with their expensive Colorado ranches, Gulfstream jets and sports cars, may be apt and well-deserved. But Grisham offers little beyond parody. He offers no credible examination of the issues raised by the explosion of class suits, nor even a hint of how we might as a society properly balance the need for compensation in large-scale litigation against the danger of windfall attorneys’ fees that dwarf the recovery for the clients.

Of course, neither Grisham nor his fans will likely pause long to consider any of this a flaw in the book. To the contrary, Grisham sells suspense, not thoughtful plot development, social commentary or even interesting character sketches.

And on this level, “The King of Torts” delivers with a vengeance. If only out of morbid curiosity, the reader is dragged through the sordid tale to its all-too-predictable conclusion. Ill-gotten gains evaporate with a change in fortunes. The FBI begins to investigate. And Carter learns what he knew all along: that some things are too good to be true. -

A shocking tale of Edison’s sleazy side

‘Executioner’s Current: Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, and the Invention of the Electric Chair’

by Richard Moran

Alfred A. Knopf, $25

On Aug. 6, 1890, William Kemmler became the first person to be executed in the newly invented electric chair. At a time when electricity was poorly understood and not widely available to the general public, the introduction of the electric chair was announced as an advancement over hanging as a more humane method of execution. Whether death in the chair is actually less painful or more humane has been debated ever since, starting with Kemmler’s own botched execution.

But there’s a story behind the electric chair. At the end of the 19th century, two emerging power companies were grappling over the emerging market for electrical power.

Thomas Edison’s direct current took an early lead but was rapidly overtaken by the advantages of alternating current offered by his competitor, Westinghouse.

In “Executioner’s Current,” Richard Moran carefully details Edison’s remarkably sleazy efforts to discredit alternating current (and Westinghouse) by developing the electric chair, covertly lobbying New York to embrace the new technology and – most important – utilizing alternating current to operate the chair. Edison then sought to disparage alternating current by dubbing it the “executioner’s current,” far too dangerous for common use.

Westinghouse took up the challenge, funding death-penalty litigation to challenge the new method of execution as unconstitutionally cruel and unusual. Both sides cloaked their less-appealing commercial interests.

Although Edison won the legal battle and the electric chair was adopted by numerous states, he lost the commercial fight as alternating current overtook direct current and became the U.S. standard for electricity. Edison’s underhanded efforts and his role as the father of the electric chair have largely been overshadowed by his contributions as the classic American entrepreneurial inventor.

“Executioner’s Current” aims to set the record straight. As this thoughtful volume attests, Edison left behind a deadly legacy: More than 4,300 people have been executed in the electric chair in the United States, more than all other methods of execution combined. And the debate over the mechanics of the death penalty still rages. -

Another legal page turner from Scott Turow

‘Reversible Errors’

by Scott Turow

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $28

Even those most committed to the death penalty usually recognize that no system is perfect and, despite all our efforts, that mistakes can be made. Scott Turow’s dazzling new courtroom thriller, “Reversible Errors,” tackles the nation’s ultimate sanction and the fallibility of our justice system.

The novel, set in Turow’s fictional Kindle County, revolves around a triple murder in a county diner for which a street weasel named Rommy “Squirrel” Gandolf has confessed after a rather difficult interrogation session. Ambitious prosecutor Muriel Wynn and gritty street detective Larry Starczek secure a conviction, and death sentence, for Gandolf.

Ten years later, as Gandolf sweats out the last few weeks before his execution date, the federal Court of Appeals appoints Arthur Raven to represent Gandolf on his last-ditch habeas corpus petition. Raven, a polished corporate litigator unfamiliar with criminal defense (much less death-penalty litigation), reluctantly takes on the case and struggles to gain vindication for what he believes is an innocent man, boxed in by seemingly insurmountable odds.

Evidence soon surfaces that might demonstrate Gandolf’s innocence, in the form of another inmate, Erno Erdai, who chillingly confesses to the crime and provides convincing evidence of his guilt just before he dies of lung cancer. The stage thus set, Raven and Wynn struggle over Erdai’s testimony, with Gandolf’s life hanging in the balance.

Raven, now fully committed to saving an innocent man from death, meets his match with Wynn, equally set on demonstrating the validity of her original prosecution, particularly in light of her ongoing campaign to become the new county prosecutor. The lightning crackles as the two clash in the courtroom, each convinced of the moral righteousness of his or her cause.

Turow unfolds a typically twisted plot, complete with bombshell developments and stunning revelations spattered across the pages. With his own death-penalty litigation experience, Turow captures that rare balance between accurate legal details and arresting plot development. Turow skillfully weaves past and present, avoiding a linear narrative and forcing the reader to continually revise the events, motives and actions that occurred on the night of the murder.

But Turow’s real strength lies behind the story, as he develops the protagonists into real people, carrying real burdens and making real choices that they sometimes live to regret. Everyone in this book has made mistakes, but only some are willing to confront them. Indeed, the novel’s central theme of redemption addresses the very line between errors that are recoverable – legal and emotional – and those that are not.

Raven, a career bachelor with no likely prospects, becomes involved with Gillian Sullivan, the judge who presided over the original Gandolf trial but was herself subsequently convicted of taking bribes and has only just been released from prison. Beaten and defeated, she struggles with her disgrace and disbelief that her crimes can ever be truly put behind her. Raven, touched by her vulnerability, struggles to build a relationship with her, uncertain how to reach her and all too aware that she could become a witness in the case.

On the prosecution side, Wynn has problems of her own. She sacrificed a once-promising relationship with Detective Starczek and married a wealthy, powerful man, only to realize as she is forced back into a working relationship with Starczek that the compromise she made may have been less to her advantage than she realized. Starczek, in turn, harbors a bitter recognition that he is “just a cop” unlikely to capture the attention of an ambitious and beautiful prosecutor like Wynn.

Erdai himself struggles to recast the past, atone for his sins and protect his own interests.

It’s a compelling mixture of carefully drawn characters that add immeasurable depth to the novel. Unfortunately, though, Turow leavens the book with unnecessarily graphic sex scenes, which actually detract from the development of the characters, add nothing to the plot, and are almost laughably drawn from an awkward male perspective. They are neither substantial (or subtle) enough to be erotic, nor passing enough to be colorful background. A stronger editor could surely have improved this text with judicious use of a red pen.

But then, why quibble? Turow is so far above the pack that, even freighted with this minor flaw, the book nonetheless easily rises above it. Turow has, by this point, plainly laid claim to the title of Master of the Courtroom Thriller. And he deserves it. -

Benjamin Franklin: An electrifying intellect

‘Benjamin Franklin’

by Edmund S. Morgan

Yale University Press, $24.95

Benjamin Franklin is perhaps the best known, and least understood, of the American founding fathers.

To the popular imagination, Franklin is remembered as a portly man who shook the world with a novel electrical experiment and authored numerous witty aphorisms. But his contributions to the political, social and scientific history of America can scarcely be overstated.

Franklin played a pivotal role in our nation’s birth – he represented the colonies in London in the stormy years leading to the American Revolution. He returned to America to sign the Declaration of Independence. He negotiated a critical alliance with the French, and even negotiated the terms of American independence.

Edmund S. Morgan brings Franklin’s larger accomplishments alive in his new biography, “Benjamin Franklin,” a thoughtful and imaginative volume that vividly recounts Franklin’s astonishing achievements.

Morgan, who was awarded the National Humanities Medal in 2000, is chairman of the voluminous Franklin Papers. He describes the book as “a character sketch that got out of control.”

It’s an apt description. Unlike the popular recent biographies of Lyndon Johnson or John Adams, Morgan doesn’t comprehensively catalogue Franklin’s life. He omits almost entirely any examination of Franklin’s personal life, mentioning only in passing Franklin’s illegitimate son (whose mother has never been identified) and his wife who stayed behind in Pennsylvania during the long years that Franklin spent abroad.

Rather, Morgan draws almost entirely from Franklin’s own writings to weave a comparatively brief (314 pages) essay on his most important contributions to his city, nation and world. It’s a refreshing focus on Franklin’s larger contributions. Morgan’s writing, fluid and thoughtful, narrates Franklin’s life in the present tense, which brings a compelling immediacy to the text.

Franklin was a printer by trade. His immense curiosity led him to constantly experiment on the world around him. He experimented with the effect of oil on water, demonstrated how the temperature of the Atlantic revealed the course of the Gulf Stream, mapped the movement of storms and redesigned common stoves.

Franklin’s experiments with electricity, conducted from 1748-50, were his most famous. Begun at age 40, the experiments explained the fundamental nature of lightning and electricity to a world that barely understood it. He proposed an experiment to demonstrate that lightning was actually an electrical charge, similar to static electricity (the only kind known at the time). This one experiment alone brought Franklin worldwide fame.

Sent to England to represent Pennsylvania in 1757, he was later appointed by other colonies and served, for practical purposes, as the “American” ambassador. In London, he earned fast friends, enormous respect and severe British approbation as the point of contact between restless colonies yearning for freedom and an angry imperial government determined to teach the colonials a lesson. Franklin sarcastically published in response a pamphlet entitled “Rules by Which a Great Empire May be Reduced to a Small One.”

Franklin was convinced that American growth would lead to power and wealth. A reluctant revolutionary, he argued that the colonies should be allowed to legislate for themselves as a co-equal to the British Parliament, both subject to one sovereign. British Parliamentary rule was futile, in his view, and would lead only to alienation and, ultimately, to the exclusion of England from America’s unlimited potential. But as the tension inexorably ratcheted both countries toward war, Franklin was unable to persuade an unyielding Parliament to compromise.

Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1775. Resigned to the necessity for war, he signed a Declaration of Independence drafted largely by Thomas Jefferson, and was appointed to negotiate a critical alliance with the French. He playfully wrote to an English friend early in the war to consider that “Britain, at the expense of three million pounds, has killed 150 Yankies this campaign, which is 20,000 a head; and at Bunker’s Hill she gained a mile of ground. … During the same time, 60,000 children have been born in America. From these data [you] will easily calculate the time and expence necessary to kill us all, and conquer our whole territory.”

In October 1776, Franklin, now 69, returned to the Continent to represent the new American government in France, borrow money and purchase supplies for General Washington’s army. He was treated with awe and respect by the French, courted by intellectuals, royalty and a seemingly endless supply of beautiful French women.

In 1782, Franklin helped negotiate the end of a war. He returned to Philadelphia in 1785, sat in the 1787 convention that framed the U.S. Constitution (replacing the Articles of Confederation), and died three years later in 1790.

From start to finish, he played one of the most central roles in creating modern America of any of the founding fathers. As Morgan concludes “We can know what many of his contemporaries came to recognize, that he did as much as any man ever has to shape the world he and they lived in. We can also know what they must have known, that the world was not quite what he would have liked. -

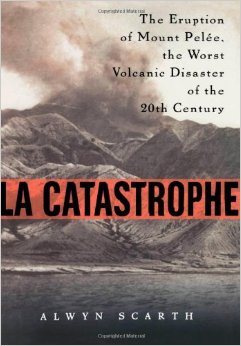

La Catastrophe’: Dramatic history of a volcanic disaster

‘La Catastrophe: The Eruption of Mount Pele, the Worst Volcanic Disaster of the 20th Century’

by Alwyn Scarth

Oxford University Press, $22

One hundred years ago, on May 8, 1902, Mount Pel -

Adventure-filled life of a local climber merits better book

‘Fatal Mountaineer: The High-Altitude Life and Death of Willi Unsoeld, American Himalayan Legend’

by Robert Roper

St. Martin’s Press, $25.95

Willi Unsoeld, the Washington state mountaineer and climbing legend, lived a life of astonishing conquests and staggering loss. It is a terrific story and one that should easily dwarf the drama of the Everest climbing fiasco recounted in the best seller “Into Thin Air.” Unfortunately, Robert Roper falls woefully short of the mark, and his thin, meandering writing all but destroys this compelling drama.

Unsoeld, one of the most accomplished American climbers of his generation, sealed his fame in 1963 with a first ascent of Mount Everest’s west ridge. He and a partner climbed over the summit with the audacious plan to cross the mountaintop and descend the opposite face, where they could meet the remainder of their party and replenish their supplies. They reached the summit at 6 p.m. Unable to descend before nightfall, they were forced to spend the night at 28,000 feet, an almost certain death sentence given their lack of equipment.

Only a freakish calm allowed their survival, and even with that, Unsoeld lost nine toes to frostbite. But he came back an undisputed American climbing hero.

Unsoeld, husband of former U.S. Rep. Jolene Unsoeld, had a lifelong fascination with the Himalayas. Indeed, he named his daughter after Nanda Devi, a spectacular Himalayan peak surrounded by a ring of forbidding and daunting mountains and cliffs.

His daughter was, by all accounts, a remarkable mountaineer in her own right. At 23, she formed a team that included her father to climb the peak for which she was named.

In “Fatal Mountaineer,” Roper recounts Devi Unsoeld’s 1976 attempt to climb her namesake. The climb from the outset was badly fractured by competing egos, by resentment from one of the team leaders that a woman was included on the climb, and by an almost reckless inattention to safety.

Notwithstanding all the obstacles, Devi Unsoeld almost realized her dream of reaching the summit. But on a precarious ledge in her tent at 23,000 feet, she became ill. After several days of battling the illness, weather and altitude, she died in the midst of a ferocious snowstorm.

Stricken, Willi Unsoeld committed his daughter’s body to the mountain and descended into a swirl of controversy over his actions, which some believe endangered his daughter.

Unsoeld, a professor at The Evergreen State College in Olympia at the time, buried his grief in his work and in teaching others his gift for mountaineering.

In 1979, he died in an avalanche on Mount Rainier’s Cadaver Gap while leading a group of novice climbers in a winter climb in treacherous conditions.

Almost any one of these elements – Unsoeld’s stunning first ascent of the west ridge of Everest, Devi Unsoeld’s tragic death climbing the mountain for which she was named or the avalanche that killed Willi Unsoeld – could have formed the basis of a compelling book.

But Roper falls short by almost any measure. The writing itself veers from pedantic to awkward, and the pacing is even worse. To Roper, almost any tangent is worth exploring, but only in superficial detail, from Himalayan religious traditions to Unsoeld’s psychological theories to mini-reviews of other accounts of Unsoeld’s climbs.

Stripped of this superfluous padding, what remains is at best a poorly written extended magazine-length recounting of the Devi climb, with a brief and incomplete summary of Unsoeld’s life appended. Some day Unsoeld’s life and death will be the stuff of a great book. Unfortunately, this book is not it.